Rising, 2020

Naturally-dyed wool (avocado pits, Aztec marigold, indigo) latch-hooked and woven into agave fiber structure.

2 x 2 m (78” x 78”)

Photo by Ramiro Chaves

Reposada, 2020

Naturally-dyed wool (pomegranate rinds, avocado pits & Brazilwood) latch-hooked and woven into an agave fiber structure

2 x 2 m (78” x 78”)

Photo by Ramiro Chaves

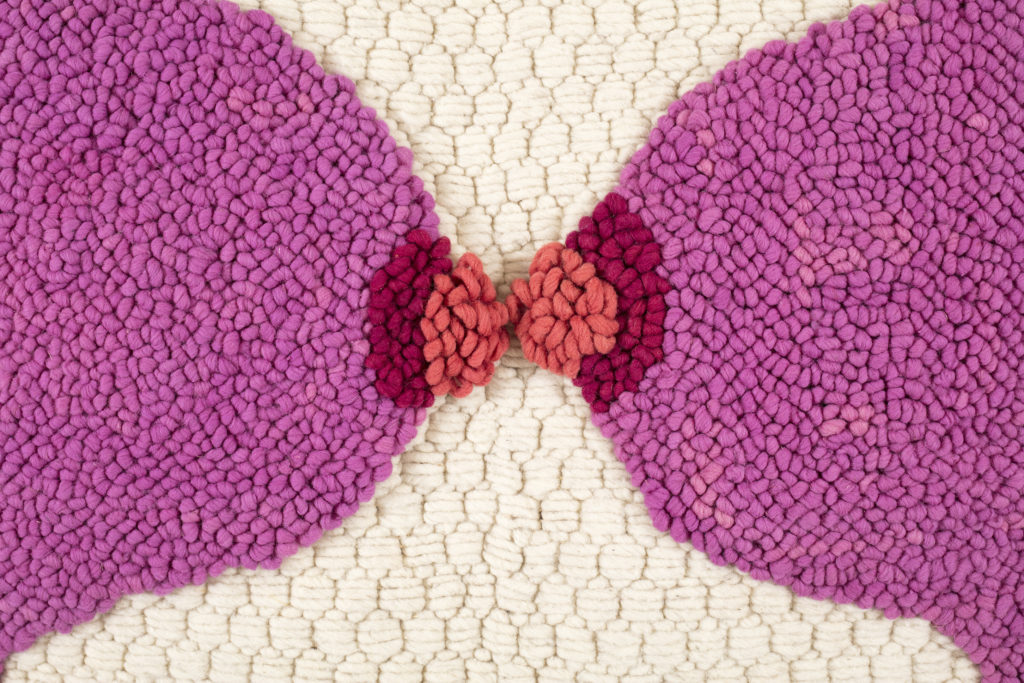

The Kiss, 2020

Naturally-dyed wool (Brazilwood) latch-hooked and woven into an agave fiber structure

2 x 2 m (78” x 78”)

Photo by Ramiro Chaves

Victory, 2020

Naturally-dyed wool (avocado pits, indigo, pomegranate rinds) latch-hooked and woven into agave fiber structure.

2 x 2 m (78” x 78”)

Photo by Ramiro Chaves

Torpedo Moon, 2020

Naturally-dyed wool (Aztec marigold, avocado pits, indigo & Brazilwood) latch-hooked and woven into an agave fiber structure.

1 x 1 m (39” x 39”)

Photo by Ramiro Chaves

LoL, 2020

Naturally-dyed wool (Aztec marigold, pomegranate rinds & Brazilwood) latch-hooked and woven into agave fiber structure.

1 x 1 m (39” x 39”)

Photo by Ramiro Chaves

Holy Smokes, 2020

Naturally-dyed wool (avocado pits, Brazilwood, Aztec marigold) latch-hooked and woven into agave fiber structure.

1 x 1 m (39” x 39”)

Photo by Ramiro Chaves

Ionic, 2020

Naturally-dyed wool (pomegranate rinds, avocado pits & Brazilwood) latch-hooked and woven into agave fiber structure.

1 x 1 m (39” x 39”)

Photo by Ramiro Chaves

Gelatinas, 2020

Naturally-dyed wool (Aztec marigold, Brazilwood, pomegranate rinds) latch-hooked and woven into agave fiber structure.

1 x 1 m (39” x 39”)

Photo by Ramiro Chaves

Transfiguration, 2020

Naturally-dyed wool (pomegranate rinds, avocado pits & indigo) latch-hooked and woven into agave fiber structure.

1 x 1 m (39” x 39”)

Photo by Ramiro Chaves

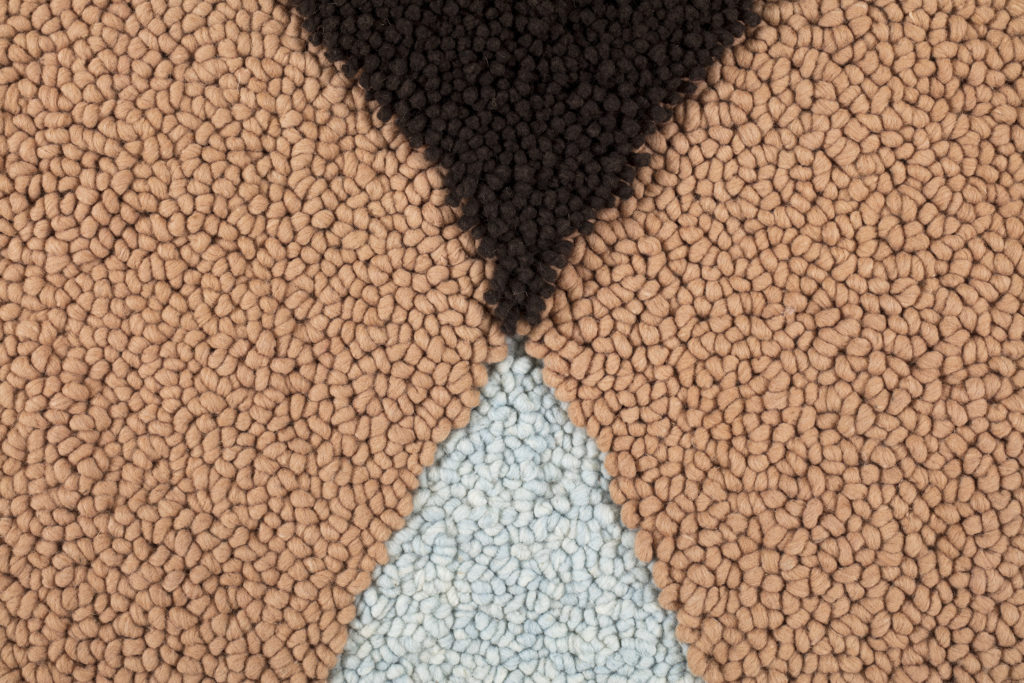

Vanishing Point, 2020

Naturally-dyed wool (pomegranate rinds, avocado pits & indigo) latch-hooked and woven into agave fiber structure.

1 x 1 m (39” x 39”)

Photo by Ramiro Chaves

Pink Panther, 2020

Naturally-dyed wool (pomegranate rinds, indigo & Brazilwood) latch-hooked and woven into agave fiber structure.

1 x 1 m (39” x 39”)

Photo by Ramiro Chaves

Choco-Concha, 2020

Naturally-dyed wool (pomegranate rinds, Aztec marigold & Brazilwood) latch-hooked and woven into agave fiber structure.

1 x 1 m (39” x 39”)

Photo by Ramiro Chaves

Luperca, 2020

Naturally-dyed wool (avocado pits, cochineal, Brazilwood, oak galls & pomegranate rinds) latch-hooked and woven into agave fiber structure.

1 x 1 m (39” x 39”)

Photo by Ramiro Chaves

TEXT

AURORA PELLIZZI’s AYATEX

by Gini Alhadeff

Aurora Pellizzi’s object-images are the result of painstaking labor, composed of thousands of small repeated gestures, much like the precise pencil drawings by Vija Celmins representing waves, or the exacting renderings of lines and grids on canvas by Agnes Martin. Her subject, the female body, is always in the presence of another though hidden current which is patience itself—the patience to which a woman is bodily subjected, from procreation to birth and breast-feeding. This lends the images a masterfully contained and rechanneled force resembling rage that ripples through the surface of the square renderings.

As with most series by Agnes Martin, the format—39” x 39”—remains the same throughout. A woman’s body is seen in perspectives rarely seen in women’s magazines —two raised thighs with a black triangle between them; a single breast under a wavy cloud of smoke from a cigarette, then an all-too human looking series of four breasts or udders, as the woman’s body finds itself perhaps transfigured into a beast of burden. The colors are fuchsia, red, light and dark grey, white, orange, brown, black, lilac, pink, blue, yellow, green and beige obtained by infusions of brazilwood, cochineal, avocado pits, Aztec marigold, indigo, and their combinations.

The yarns used throughout are from Mexico and the works, devised by Pellizzi as to number and placement of stitches, colors, and base canvas, were then made with a cooperative of weavers in the State of Mexico in a series of collaborative sessions throughout the months of pandemic lockdown in Mexico. The techniques employed were developed with the weavers themselves—Ibeth Meliton, Margarita Librado, Valeriana Gutierrez, Maria de Los Angeles Gutierrez, and Jaquelin Hernandez—in a temporary workshop set up in one of their homes. The object-images were made of naturally dyed wool, volumetrically woven and latch-hooked onto a supportive web called ayate, a pre-Hispanic garment/accessory hand-woven on backstrap-looms out of handspun maguey or agave fibers. The most famous ayate was the cloak of a man later sainted on which the Virgin of Guadalupe is said to have miraculously appeared in 1531. To this day ayates are used to carry firewood, corn, and other agricultural products in the Mexican countryside. The ayate offers a loosely woven surface, and the thick yarns, after having been dyed with natural dyes, are hand-woven through the net, one by one from with a needle at varying lengths of looping. This produces a tactile relief effect on the surface of the images.

Tina Modotti showed in her 1971 portrait of Frida Kahlo that a woman can have hair on her upper lip, and unlike a more American feminine esthetic of hairless bodies, the close-ups of figures represented here do have hair in their armpits, and at the triangle that is the origin of the world. The triangle in Aurora Pellizzi’s hand-woven object-images is both sensual and rigorously geometric. It is this pairing in all the works that brings them to vivid attention. The use of embroidery, crochet, knitting and other “sissy” crafts, as the great artist-weaver Anni Albers once termed them before she saw that they could “rise to art,” in contemporary art evokes the work of Ghada Amer—her delicate fine-threaded embroideries of images taken from pornographic magazines—or Rosemary Trockel’s knitted works.

Born in Mexico, Aurora Pellizzi grew up between the states of Morelos and Chiapas, and in New York City.

The project provided a secondary source of income for the weavers, creating a point for collective work and communion compatible with their daily chores and tasks of home-tending and mothering. Gatherings for the project also created opportunities for conversations and exchanges on the subjects of maternity, sexuality, and representations of the female body.